Dr Jonathan Barnes writes exclusively for Staffroom about a learning environment for participation and engagement as part of our ‘New National Curriculum’ issue.

We each respond to environments differently. Even identical twins sharing the same physical, social and emotional world occupy according to Pinker, ‘a unique environment’ (Pinker 2002). What curriculum and teaching choices therefore could possibly create the physical, educational and emotional atmospheres in schools that promote challenge, participation, engagement and learning for all children?

Research and the experience of 40 years in primary and secondary classrooms tells me that motivation for all has arisen most frequently as a result of cross-curricular approaches. By cross-curricular learning I mean that promoted by making links between the attitudes, skills and knowledge across two or more curriculum subjects.

Cross-curricular teaching involves planning, arranging and assessing learning situations where two or more subject approaches can be applied to a single and authentic experience. Good cross-curricular learning cannot happen without reference, back and forward, to detailed and extensive separate subject knowledge.

Cross-curricular links are not mentioned in the new national curriculum (DfE, 2013), but this does not mean they are disapproved of. In its aims and structure sections the national curriculum reminds schools that:

The national curriculum is just one element in the education of every child. There is time and space in the school day and in each week, term and year to range beyond the national curriculum specifications..[It] provides an outline of core knowledge around which teachers can develop exciting and stimulating lessons to promote the development of pupils’ knowledge, understanding and skills as part of the wider school curriculum.[and] Schools are free to choose how they organise their school day, as long as the content of the national curriculum programmes of study is taught to all pupils. (DfE, 2013, p.6)

Children of all ages benefit from exposure to the links that can be made across the curriculum and beyond. My own research has dwelt on cross-curricular approaches that positively affect learner motivation and application. We know that not all pupils are ready to be motivated. Factors well beyond curriculum affect a child’s mood and readiness to acquire knowledge, skills and understanding in a school context. The widely differing sets of environments that each child encounters can either limit or encourage positive attitudes towards school learning.

No school environment could promote 100% engagement, but there are conditions that make it more likely that children will be involved and supported in meaningful, deep and transferable learning. Good cross-curricular learning should of course provide real challenges and be, useful, constructive, empowering, flexible and lead to a thirst for more. The path to such learning is eased when we as teachers help construct environments within which all children can flourish and learn.

The environments that influence learning in school settings fall under six headings:

- The values environment

- The physical environment

- The social environment

- The emotional environment

- The cultural environment

- The curricular environment

These environments overlap and are interdependent. Teachers play a major part in establishing, maintaining and controlling them – usually without thinking about it. This article will suggest that teachers should carefully consider the environments they create and use, if they want to engender positive attitudes to learning. Each environment has cross-curricular implications.

The values environment

The values that underpin a school shape its whole character. A value is a fundamental belief that directs our actions in the world (Booth and Ainscow, 2011). We arrive at every setting with an established set of values that influence our decisions large or small. For a child, actions as minor as picking up a pencil or as important as entering the learning journey at all, result from their emergent values and those of the people around them. Fundamental beliefs tend to be formed in the school years and turn out to be very hard to shift after teenage (Gardner, 2000; Barnes, 2013).

The early birth of values suggests an important role for teachers in helping children develop morally good beliefs. In practice values formation is given little curriculum or staff development time, yet Oftsed consistently highlights the relationships between clear well-communication and quality education.

Teachers may find their values conflict with those of their pupils, but they are in a position to establish a shared system of values that significantly impact on children’s present and future self-image, relationships and attitudes to learning. Before considering curricular approaches, therefore we should consider the values-context within which our curriculum will sit.

Our most profound beliefs apply across all aspects of our lives. If we truly value such things as community, mutual respect, equality or excellence, then those values will be apparent in our home life as well as the choices we make in school. Teachers are dedicated to communicating knowledge, to championing its excellent application, but they are also committed to children and childhood. There is no conflict therefore, between teacher’s typical espousal of ‘soft skills’ like respect or caring and a passion for high standards in learning – good teachers believe in both. Teachers’ experience of children tells them that they live life more ‘in the present’ than adults, they play more, do more are usually more active and practical than adults.

Childhood typically is freer from the pressures of planning for the future or worrying about the past. An environment that regularly demonstrates inclusive and instantly recognisable values like love, joy, trust, fairness, respect, generosity, humility, collaboration, dignity, hope, participation and belonging, has a particular resonance with those that live in the present.

Inclusive values apply across the whole curriculum. Humility might be shown in geographical, historical, language-based, movement and artistic contexts; hope can have mathematical, scientific, technological, religious and musical expressions. Every value has curriculum illustrations as well as potential expression in the daily lives of the children. The examples below show how some schools address values in cross-curricular ways.

The physical environment

Physical surroundings and the objects within them influence our mood and perceptions. Damasio from a neurological perspective claims that, ‘few objects in the world are emotionally neutral,’ (2003, p. 56), suggesting that the furniture, decoration, equipment, even the view from a classroom can have a unique and highly personal impact on our thinking. If even classroom chairs mean something subtly different to each person, then artefacts, constructional or decorative details, the trees in the playground or the spiders under the windowsill can become rich sources of engagement. A field trip to the wild area of the playground might become transformative.

The more displays and exhibitions enhance classroom walls and spaces, the more children work outside the classroom, the greater the chances of engagement. Diverse, multifaceted experiences that speak to all the senses, making connections across the whole brain, are seen by neuroscientists as fundamental to school learning (Goswami and Bryant, 2007; Sousa, et al, 2010).

The sensory environment matters. A school’s physical surroundings: its views, locality, playground, corridors and classroom, constitute the ‘real’ world for the children. Taste, smell, touch and fine distinctions of sight and sound are very much part of that world for children and should therefore be used to engage and focus their attention across all subjects in the curriculum. We should map smells, calculate the number of different greens, describe different tastes or compose sounds that express textures, reflect on the sounds in the wild area.

The environments in which we learn are major resources for learning. Every aspect of the physical environment is open to cross-curricular thinking. Take the chair you are sitting on. It was designed, probably drawn first, mathematics would have been applied to the detail of its construction and purchase, the sciences of forces, materials and a detailed understanding of the human body would have influenced its prototype, and specialised language must have been used throughout its commissioning, construction and distribution. An analysis of the trees in the grounds, the pictures on the walls, the clothes we wear and the artefacts on display would yield a different, group of subject understandings that combined to produce them. Equally chair, tree or artefact can be represented and understood through the eyes of many, perhaps all, curriculum subjects.

We should get out more often. School visits to the street, museums, concerts, forests, supermarkets, towns and landscapes adds to the wealth of cross-curricular contexts for learning. Consider the examples below.

The social and emotional environment

Most children learn socially. Perhaps because of the unique environment they inhabit it is often clear that they see the world in different ways and have different skills and fascinations from each other and ourselves. This combination of our natural desire to be together and the essential differences between each brain creates a powerful setting for original and creative thought. The very difference between children can become a resource in itself and a powerful source of motivation, but differences need to be allowed and celebrated to utilise this resource fully. Children arrive at school with a wealth of social knowledge from family and community – it must not be ignored or belittled.

Social learning in the school starts in the playground. The greeting parents and children receive as they enter, the atmosphere that dominates play in the yard and the ways children interact when they meet each other have their effects all through the day. Similarly social learning in the classroom begins with the welcome children receive as they enter the room. It is expressed in the furniture. In primary schools it is common to see tables arranged in groups, but this practice is increasingly challenged as pressures mount to meet subject knowledge targets rather than goals linked to a deeper understanding gained by collaborative, active and social approaches.

There is not one way to arrange a classroom to promote good learning, indeed the key is flexibility of approach. Music in song and with instruments may require a circle of chairs, expressing the collaborative nature of music making, map work in primary geography may be best done in groups of four, some individuals might like to work alone and some lessons might be better received in rows and others in groups of six of eight. If we are prepared to move the furniture frequently we maximise the chances of accommodating different learning preferences.

The social character of the classroom overlaps with its emotional quality. Personal emotions direct behaviour, control learning, define relationships and profoundly influence health and well-being (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007). Unfortunately the arts and humanities, which identify, exercise and develop emotions like empathy and sensitivity, are often marginalised in systems that overemphasise simple knowledge acquisition. Individual intellectual and mental well-being relies upon a balance between ‘right brain’ activities, that connect individuals emotionally to self, others, things and places, and ‘left brain’ approaches that are more dispassionate, logical, structural and mechanical (McGilchrist, 2010). Cross-curricular teaching and learning at its best gives opportunity for both kinds of mind to be applied to a single experience, problem or issue. In such a context children appear happier.

When we are happy we learn better. Scientific claims that positive emotions provide optimal conditions or learning. (e.g. Immordino-Yang and Faeth 2010) have become common as child and adult well-being has risen up the political agenda. Positivity also appears to broaden and build our ability to make relationships, think creatively, integrate past experience with the present and extend our physical and mental abilities (Fredrickson, 2009). Both motivation and disaffection have emotional starting points and if we want to promote learning research suggests that we work towards establishing emotional environments of security, trust, curiosity, enthusiasm and mutual respect.

The inclusive values listed earlier aim to promote supportive communities. Collaboration, joint problem-solving, participation and relaxed communication are also involved in inclusive attitudes and point towards group tasks and challenges. But inclusive education is not simply expressed in the arrangement of furniture, but in the kind of tasks children are asked to involve themselves in. Inclusive teachers choose tasks that feel authentic and relevant to the children often as a link to areas of learning that may initially seem irrelevant. Children often say they find socially and emotionally relevant activities more engaging and sustainable. In group work the different perspectives each individual brings are celebrated, this is inclusive behaviour, but each differing response also enriches understanding and promotes transferability for all participants. The meeting of differences is a key attribute of creativity.

Creativity is a defining feature of human behaviour. When we recognise our own ability to use our imaginations, to make something original or to contribute a fresh and useful idea we generally feel good. Creative learning happens where new and imaginative ideas arise from bringing together different materials and mindsets and cross-curricular approaches are therefore often linked with creativity. Check the summaries below for examples of cross-curricular teaching and learning that relies on social and emotional dynamics.

The cultural environment

Each child belongs to many cultures. Culture, defined as, ‘the shared values and patterns of behaviour that characterise different social groups and communities’ (National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE ) 1999, p.47) provides an important sense of security of belonging. If teachers want their children to identity with the culture of the classroom it should relate to the cultures children already belong to: family, faith or friendship group, social class or ethnic background. Relationships to other less defined cultures: ‘high culture’, ‘British culture,’ intellectual culture, are also part of the role of the school and are best established through gentle exposure, visits and visitors.

It is easier to help pupils participate in a wider culture when they are linked socially, philosophically, morally, or through arts, sports, language and authentic experience to the world beyond the classroom. Engagement with the wider world may involve confronting complex and difficult issues bigger than the curriculum itself – environment, faith, community, sustainability, peace, social justice, but as Alexander (2010) and others maintain that the rewards are great. The research (e.g Roberts, 2006) constantly shows that pupils are better-motivated, better-behaved and better learners when exposed to real sites, real individuals and new situations. Again the analysis of real situations, behaviours and beliefs is central to good cross-curricular practice. Visitors, field-trips, visits to museums, galleries or stadia are never single subject affairs, they almost always generate questions and insights outside the expectations of the teacher.

Since most of the made world is a product of teamwork and cross-curricular thinking, it is appropriate that we make sense of it through the eyes of the key subjects involved in its creation. A visit to an art gallery supports learning in art, but just as powerfully could be the start of a design or a music composition project, a field trip to a forest is as useful for learning in science as it is in geography, but could it be used as the stimulus for new ideas in dance choreography or drama?

The curricular environment

The curriculum environment is the one most suited to providing the best intellectual environment for every child. I have argued that cross-curricular settings are more inclusive, provide more motivation and more accurately mirror the real world, but my research (Barnes 2015, in press) has identified at least seven different modes of cross-curricular learning:

- double focus

- life skills

- tokenistic

- hierarchical

- multi-disciplinary

- interdisciplinary

- opportunistic

All modes operate within the environments already described, but each has a different objective. Each cross-curricular approach has its own distinct effect on the environment of the school. Some are formal, some very informal, but all are united in their recognition that the world is a complex place which we can understand most fully through the application of the subject disciplines. In real life the disciplines are very rarely applied singly. It is in combinations of insights, in connections between widely different mindsets that our world and our minds have been shaped. From the classical philosophers onwards cross-curricular teaching and learning has expressed the connectivity we see in the environments around us.

Separate subject knowledge is essential to good cross-curricular learning. It is not however true that pupils cannot learn in cross-curricular or creative ways until after they have had years of subject teaching . The teaching of discrete aspects of subject knowledge and their application in cross-curricular contexts can be achieved in the same week. A primary school week could for example be divided between 66% of time spent on exciting, creative and relevant separate subject teaching and 33% spent on the cross-curricular application of some of the new knowledge, skills and understanding gained through separate subject teaching.

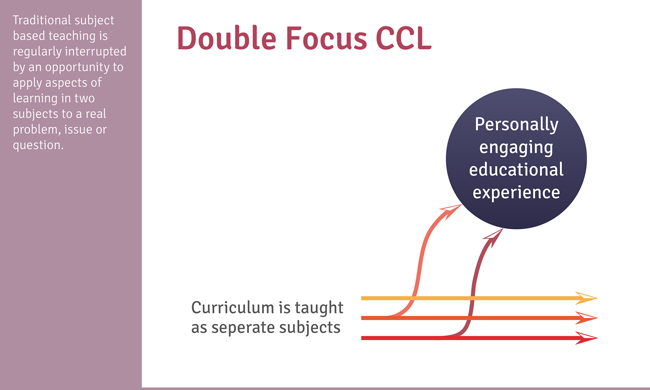

Through a school year (perhaps once every six weeks) it is possible to apply new learning in each curriculum subject in a cross-curricular context. This approach I call double focus because of its reliance on two different modes of learning. The focus is jointly on ‘pure’ or traditional subject teaching and also upon cross-curricular opportunities to put learning into practice. The double focus should apply to all kinds of cross-curricular learning. An important feature of each of the approaches itemised below are personally engaging educational experiences, like practical work, visits and visitors.

Only two curriculum subjects, plus always English, are marshalled to help throw light on the experience. Through many years of working in this way I have found that applying more than two subject foci to a single experience results in confusion and always provides difficulties in ensuring appropriate subject progression. In the secondary school the double focus may be more difficult to maintain throughout the year, but is successfully employed in schools that deliver a thematic curriculum in years 7 and 8 or who mount themed weeks during the year.

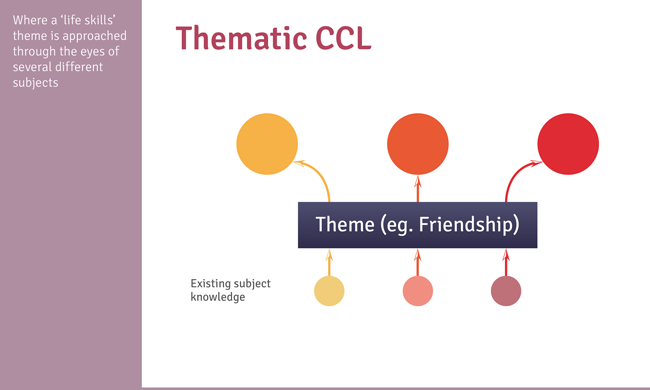

Thematic cross-curricular approaches, such as that used by the Royal Society of Arts Opening Minds Curriculum (RSA, website) address the whole curriculum in both primary and secondary schools through themes related to life skills. The RSA themes are: citizenship learning, managing information, relating to people and managing situations. Similarly the International Baccalaureate (IB website) units on the theory of knowledge and action/community service involve the application of learning across a wide range of curriculum subjects. Other schools may take broad topics like: friendship, caring, my home, water, myself, and apply a different subject perspective week by week. The key to good cross-curricular approaches is ensuring transferable understanding and progression in each of the subjects used.

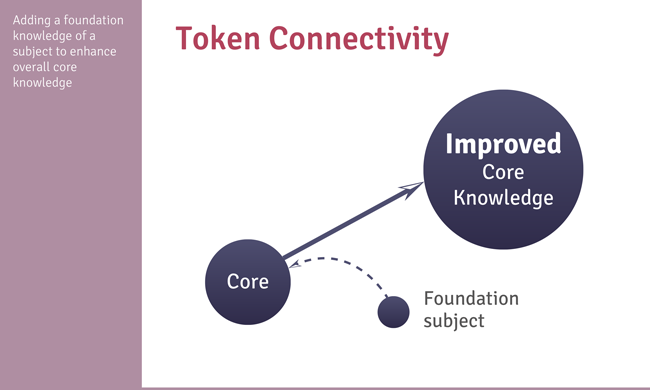

There are however less successful modes of cross curricular learning. Some approaches sadly are merely tokenistic, they make a gesture towards simultaneous learning in two subjects but fail to add anything new to one of them. For example a teacher with a year six class might ask them to sing ‘heads, shoulders, knees and toes,’ (perhaps for the hundredth time in their lives) to introduce a lesson on the human skeleton. It is likely to have taught the children nothing about music.

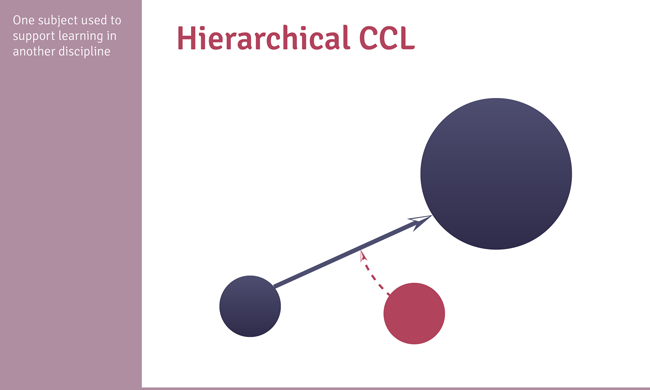

Sometimes however teachers legitimately adopt a hierarchical approach to cross-curricular learning, giving pupils a chance to exercise some new learning on one subject in order to enhance learning in another.

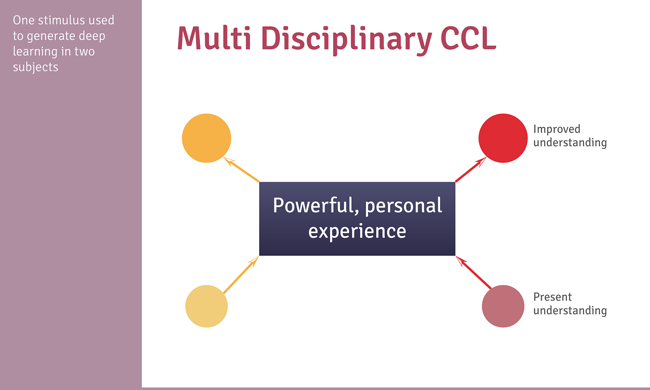

Many of the examples of cross-curricular teaching and learning used in this article illustrate what I call multi-disciplinary cross-curricular learning. Learning is multi-disciplinary when specific learning in two subject areas arises from a single experience. The two units of learning are developed separately after the initial stimulus but both throw equal light on the experience.

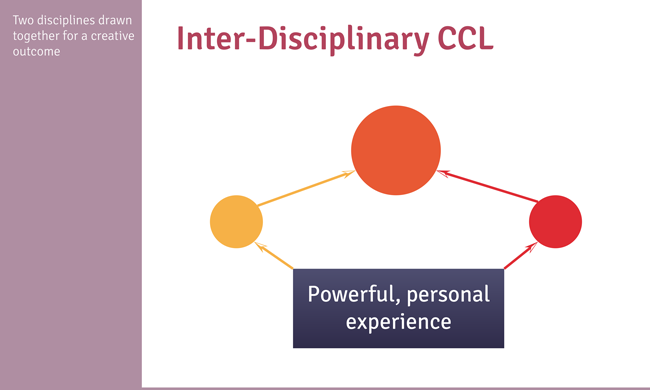

Cross-curricular work with a creative intention is often inter-disciplinary. With inter-disciplinary cross-curricular learning, new knowledge and skills in two subjects is combined to make something new, valuable and imaginative. The subjects involved are intermingled and dependent upon each other in some kind of final product.

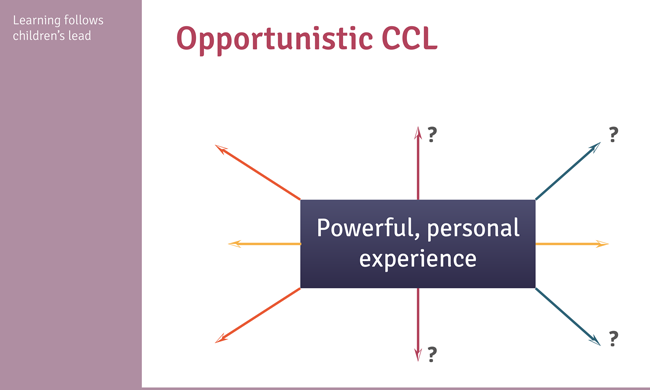

In Children’s Centres and nurseries cross-curricular methods are common. With such young children, for whom play is a crucial learning mode, their nursery teachers follow the lead given by children’s own interests. Perhaps the child has found a nest in the school garden and wants to know what it is, or has observed the accidental mixing of paint colours in the sink and wants to understand.

The teacher will be on hand to answer the questions and perhaps lead the child on to consolidating the answers. This opportunistic approach to teaching and learning allows children to dictate what they want to know. It matches learning to the time and place where children really want to know the answers to their questions and arises from teachers giving them space to play and explore freely.

I have outlined and illustrated seven contrasting modes of cross-curricular teaching and learning. Each has a different intention and involves different methods, but each is an attempt to break out of the narrow subject silos that suggest leaning is simply a matter of remembering facts and learning de-contextualised skills. Good, flexible, useful and relevant learning is too important to leave to chance. Children do not learn in the same ways as each other, neither do they get excited or curious about the same things. Their present experience of the world provides the foundations of everything they will contribute, be and feel in the future – schools have a duty to make the child’s present as motivating fulfilling, positive and good as is possible. SR