World-renowned education professor, Guy Claxton, shares his thoughts and experiences on growing independent learners – exclusively for Staffroom.

Last week I was in an audience of around 60 educators, watching a demonstration lesson in St Bernard’s Catholic Primary School in Ellesmere Port in Cheshire. In front of us were about ten Year 5s, miked up so we could eavesdrop on their discussions. They seemed completely unfazed – not at all inhibited by this odd experience. We all watched an elegiac little animation called ‘The Piano’, and the children were first asked to ‘explore the deeper meanings of the film’ in conversation with their partners.1

They quickly uncovered two good questions: “What triggers reminiscence?†And: “What, in art, makes for an effective ‘flashback’?†The next question their teacher asked them made my ears prick up. He said: “Where do you want your learning to go from here?â€

The children decided they wanted to explore the second question and, in discussion, generated a list of success criteria for a good artistic or literary use of a flashback. We went to look around the school whilst the children wrote their own version of a flashback for themselves. When we came back they read them out to the whole room – again without any self-consciousness.

One piece, by Fiona, who wanted to be a writer when she grew up, was superb. The teacher said: “That was good, Fiona. Now, who could find a way to offer Fiona some feedback that would help her make it even better?†Immediately several children offered, very respectfully, some tentative suggestions for improvement.

The teacher asked Fiona: “How did you feel, getting that feedback?†She said: “At first I was a bit hurt that they were not more impressed, but then I remembered they were just trying to help me make the story the best it could be, and then I felt grateful for their ideas.â€

These children’s astonishing confidence, insight, creativity and respect for each other wasn’t a reflection of their home backgrounds. Many of them came from complex homes and/or disadvantaged backgrounds. Their qualities of communication, collaboration, imagination and presence of mind came from months of deliberate coaching by the staff.

One of the key aims at St Bernard’s is ‘to help the children build transferable skills and attitudes for lifelong learning’ – and they are conspicuously successful. Everyone in that audience was deeply impressed, and a good many of us were moved, by those ordinary children – with extraordinary learning habits and dispositions. Their learning would have been outstanding even in a group of bright sixth-formers. And, by the way, the children’s levels of attainment, and a recent Ofsted, are both Outstanding.

St Bernard’s is a Building Learning Power (BLP) school, and I was there to celebrate their becoming one of the very few schools in this country to gain the BLP Gold level Award.2 But all over the UK, there are hundreds of schools making demonstrable progress in their quests to coach good learning habits: the habits that will underpin success in school exams, success in the much more independent world of college or university (where too many high- as well as low-achieving students currently fail or founder), and success in pursuing their own passions and dealing well with the unpredictable challenges of the real world.

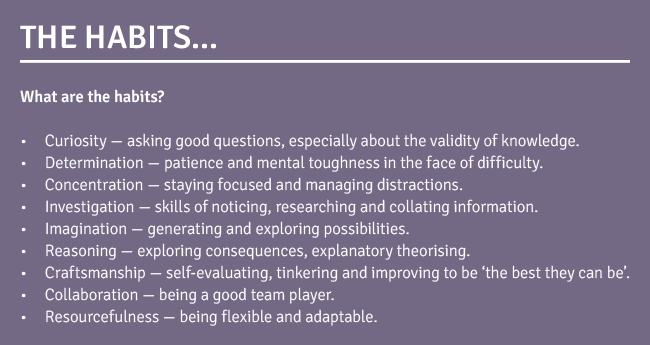

The basic habits of powerful learners are shown above. Within each of those broad categories, you can go as fine-grained as you like. At St Bernard’s they unpick the general area of collaboration, for example, into a host of more specific skills and attitudes: active listening, explaining ideas clearly, validating others’ contributions, standing your ground, building on others’ ideas, turn-taking and not talking over people, staying focused on the topic, monitoring and if necessary helping to improve the workings of the group, giving feedback and suggestions respectfully, seeking and accepting feedback graciously and so on. Each of these, and more, are given explicit attention repeatedly in the course of ‘normal’ lessons.

The maturity of those kids in the hall, naturally manifesting many of those detailed facets of good collaboration (under the pressure of being observed by dozens of unfamiliar eyes) is the fruit of that explicit, painstaking coaching, carried out across the whole school.

To build that level of skill amongst a whole staff of teachers (and teaching assistants) takes time and clear, relentless leadership. People are being asked to adjust their habits, some of which they may not even realise they have – such as talking in a way that discourages a growth mindset, as Carol Dweck has shown.3

And that takes patience, support, coaching and a clear appreciation of why this is worth doing.

Those people in that hall who were new to BLP were blown away by what they saw. They went away convinced that building powerful learners is a deeply desirable goal of 21st-century education – and, more importantly, one that is eminently practical and possible. SR