We teachers spend hours and hours marking pupils’ work, only to hand all that rich data back to students. What do we hope students will do with the marking?

They are likely to compare their marks with other students, and either feel good about themselves or disheartened. What about the comments diligently made by the teacher in order for the student to improve?

In reality, no matter what your lead team have asked you to do in their marking policy, these constructive comments are often ignored and regularly go without any action on the part of the student.

Strong feedback is timely, specific, actionable (pointing students in the direction of more information) and useful. Students are given opportunities to re-learn and practise the skill again right away.

To feedback well is to “feed forwardâ€. That is, as teachers we should ask ourselves: how will I use what I learned in the feedback process to inform my teaching?

Feed forward helps us anticipate misconceptions and decide what needs to be re-taught and to whom. Too many teachers fail to (a) track their feedback, and (b) use the data to alter their upcoming lesson plans.

Many schools are looking to update their marking policies in light of the recent emphasis by Ofsted on students’ books and files as evidence of “deeper learning†and “rapid and sustained progress … over timeâ€.

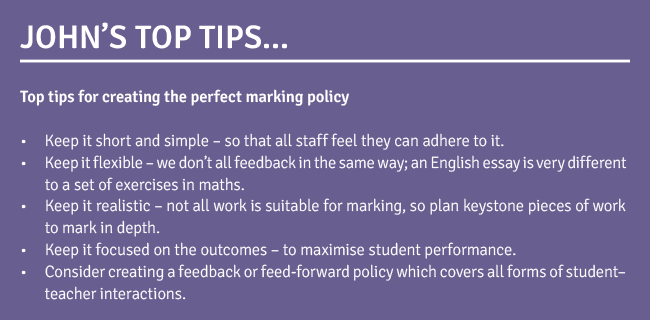

I would advocate moving from a marking policy to a feedback or even feed-forward policy. I’m actually not a big fan of educational jargon, so it doesn’t really matter what a school calls its policy as long as the ethos of why we mark is fully understood by staff and pupils alike.

I often ask teachers to complete what appears to be a simple ranking exercise in my training courses to justify why they mark. This often causes a polarisation in groups, as some teachers interpret this as why should they mark, rather than why do they mark.

There are numerous external pressures in schools which compel teachers to mark in a certain way for a certain audience: many teachers mark because there is an upcoming learning-walk or book scrutiny, or because it is school policy to do so.

For marking to be truly effective, it must be seen as part of a process whereby we use assessments to inform the next steps in our teaching, so in essence it should involve feeding forward.

Many schools are still stuck in an older model of planning lessons, teaching them and then marking the work, when really it should be the other way round. Marking the work allows the teacher to “plan astutely†(to use more Ofsted speak) and then teach more effectively.

They do not expect every subject or phase to follow exactly the same procedures, but rather set an expectation for an approach in each context. It would be very difficult for a maths teacher to provide feedback in the same way as a teacher marking English written work.

They will also give guidance on the regularity of marking, and they often suggest different levels of detail in marking. It would be impossible and unproductive to mark every piece of work in the same depth; an appropriate balance needs to be struck in each subject and school context. For example, some primary schools have one focused piece of written work each week, and on the following day allocate time for feedback and for pupils to respond to marking. Any policy must have the students at the heart of it.

Encouragingly, when asked why they mark, most teachers will describe a positive impact it has on their students’ learning, progress or independence.

I’m heartened that individual teachers have not lost sight of this, as many school policies and book scrutinies have become box-ticking exercises based on what we imagine Ofsted will expect when they visit. In reality, we don’t mark for Ofsted or for our leadership teams; we mark because we believe it improves individual students’ understanding and progression.

Ofsted focus on the outcomes of our marking, not the format, and do not expect a certain style. They will triangulate their decision based on lesson observations and discussions with pupils in order to assess its impact on learning and progression.

Where teachers set work using clear objectives, learning intentions and success criteria, marking is more focused, more useful to learners and quicker for the teacher. It is often true that those who spend a long time marking were not clear about the purpose and intention of the task in the first place.