Almost four decades on from the introduction of comprehensive schools, the battle of opinion rumbles on…

In Kent, parents and councillors continue their fight to open a new satellite grammar school. They have been told by Government that the site must be used for a free school.

And in Chelmsford, a top-performing grammar school is introducing a new selection process and scrapping the 11-plus in order to alleviate pressure on pupils from private tutoring.

Grammar Schools

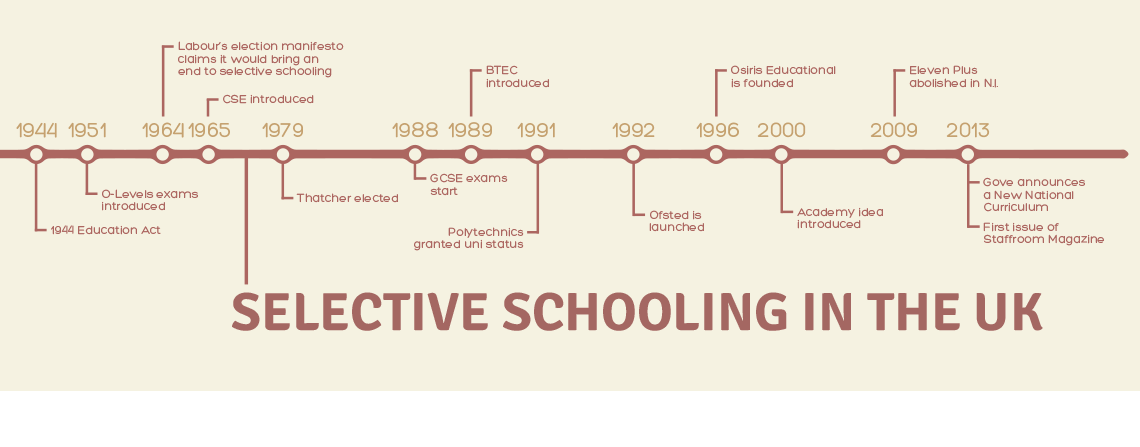

There are currently 164 grammar schools in England and 69 in Northern Ireland. The 1970s witnessed the gradual transfer to comprehensive schooling, scattering behind a few anomalies that resisted the transition.

To this day, selective schooling makes for a hot legislative debate and the focus is always the same: does selective schooling still have a place in 21st-century society?

Grammar schools are not randomly strewn across the country. Instead, they tend to be found in more affluent and politically conservative areas.

Originally, the selective schooling model was intended to promote social mobility by giving poorer children access to a better education. Yet recent evidence suggests that social mobility has declined over the last 20 years, citing high prices, taxes and inflation as acknowledged impediments.

Nowadays, only 1- 2% of students at grammar schools are eligible for free school meals. In addition to this, the tutoring culture is thriving to such a degree that ministers are looking to implement a tutor-proof exam for 2014, as many children are now being coached to pass. It is said by some that grammar schools are now becoming an obstacle to social mobility rather than a vehicle for it, as it is the wealthier sectors that can afford the extra tuition.

Fierce Competition

Some areas have reported 13 applications for every place, stretching catchment areas to breaking point and forcing some children to travel 20 miles each way, each day to attend school.

The result is that good comprehensive schools are being overlooked. Then there’s the whole debate about whether a child should be subjected to a selection process that can brand them a success or failure at such a young age.

Mindset

In view of Carol Dweck’s Mindset theory (see page 16) – and in educational psychology in general- branding a child in this way can leave its mark for the rest of their lives.

Dweck’s opinion is that either outcome induces a fixed mindset in the student, making them feel superior or inferior at a crucial stage in their lives. She also believes that selective schooling creates a divide in communities and in the minds of some, making children feel that they belong to the elite or to the mediocre, generating issues of too much or too little self-esteem.

One of the recognised merits of ability streaming is that there is less variance in initial capability, and therefore the brighter pupils are not impeded by their peers. In spite of this, John Hattie’s Visible Learning study gives ‘ability grouping’ the low effect size of 0.12 and ‘ability grouping for gifted students’ the more modest 0.30, showing that in comparison with the effect size of ‘self-reported grades’ at 1.44, ability streaming matters little in terms of effect.

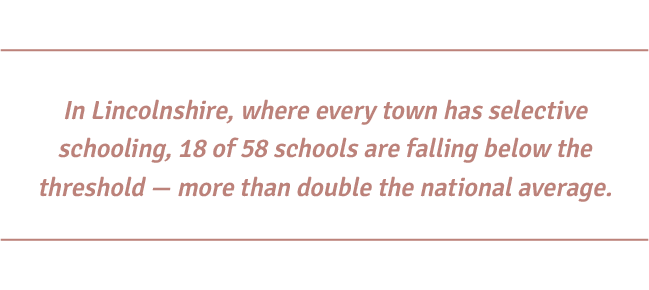

Whether you are of the opinion that selective education is something positive or negative, the fact remains that 164 grammar schools still exist in England, across 15 regions. These areas must still meet the governmental floor target of getting 50% of students through their GCSEs with 5 A* to C grades, even though the schools do not have the same mixture of ability as every other school in the UK. If the higher 25% are creamed off the top, then on paper the comprehensives do not have those students to boost up their figures, creating more failing schools.

In March 2013, the 11-plus was officially discontinued in Northern Ireland, following their Education Minister’s dismissal of selection as “outdated and unequal†in 2008.

Is it time that England followed suit? SR