The word ‘differentiation’ has been on the lips of teachers, school leaders and inspectors for well over 20 years, and yet there is still widespread debate and significant confusion over what the term means for school policy and classroom practice.

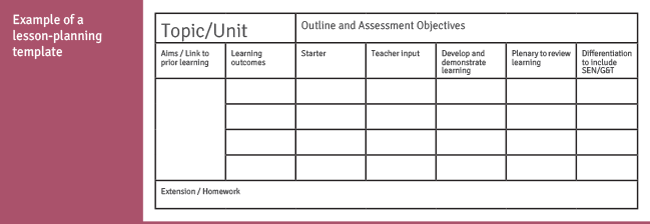

Nowhere is this confusion more evident than in lesson-planning templates like the one below used by so many schools and teacher training institutions:

Such forms usually contain a box for differentiation, sometimes (like this one) at the end of a column, and sometimes (in the portrait-style forms) at the bottom of the page. Such forms seem to suggest that teachers should plan the lesson and then add something which indicates how differentiation will be applied. The thinking behind such forms is totally misguided, and not just in relation to differentiation.

The best description of lesson planning like this is ‘teaching by numbers’, although the terms ‘straitjacket’ and ‘formulaic’ also come to mind. The three-, four- or five-part lesson with both a starter and a plenary has become in many schools a set-in-concrete rule. I have even heard of teachers being told by senior leaders: “your lesson would have been Outstanding if you had used a plenaryâ€.

Student teachers are invariably instructed in their training courses to adopt this lesson structure, and as a result learners in many schools, with a six-period day, will experience 5,700 starters and 5,700 plenaries in any five-year period, reducing teaching and learning time in that same time span by up to two years or more. What nonsense!

Why do it? The argument is that the starter helps to ensure lessons begin with settled and focused learners, and the plenary allows teachers to draw together the learning that has taken place and demonstrate progress.

For schools with poor behaviour, such rigid lesson starts might be worthwhile – a stage in a process of change designed to create order and conformity. Similarly, some teachers need a highly structured lesson form to help them plan lessons more effectively. But to ask all teachers to do this because a few are failing is not differentiation in the staffroom! Moreover, for schools not struggling in this way the rigid start is often a barrier to effective learning.

In food technology, for example, students arrive with their ingredients, clearly focused and ready to start cooking. If the teacher is forced to have a starter, then the middle part of the lesson may involve talking about what they would have cooked had they had the time!

What is the purpose of a plenary in an Art or ICT lesson when the learners are all at different stages on a range of designs or assignments? Why require a teacher of English to have a plenary at the end of a lesson when the class is still reading the play?

Why not trust the teacher’s judgement that it is far better to have the review of understanding halfway through lesson two when the reading has been completed?

A more productive approach based on simple common sense is for schools to formulate a set of rigorous principles for Outstanding teaching, learning and assessment that allows teachers to choose the best methods for meeting them. The way in which teachers of Early Years meet the principles will be different from those who work with Year 6.

Teachers of Physical Education may use different strategies from teachers of Science. The same teacher working with Year 7 may adopt different methods with sixth-form students. The principles are the same, the approaches varied. Consistency prevails rather than conformity.

What kind of principles am I suggesting? The schools I have worked with on this have personalised them, but they all focus on key issues.

For example:

“All lessons begin with the purpose of learning clear to all.”

Some teachers will use a starter to achieve this. In subjects like Art, D&T and Music, or any lesson where students are in the middle of a project, the teachers expect the students to start work on arrival, with personal logs or record sheets providing the purpose of learning.

For example:

“There will be regular review and celebration of progress.”

Some teachers will decide to have a plenary at the end of a lesson. Teachers of Mathematics, however, may ‘chunk’ the lesson with some classes, and have six plenaries in an hour, reviewing understanding and skills every ten minutes, getting feedback that allows them to pace the lesson correctly with weaker students.

The principles approach has been adopted by many of the schools that I have worked with on training, and it has the potential to transform classroom practice, particularly in terms of differentiation which I define as “intervention designed to maximise the learning and progress of all studentsâ€. So, “differentiation by outcomeâ€, where no intervention takes place, is in my eyes not a real strategy and the phrase should be banned in schools. When schools adopt key principles for teaching, learning and assessment, differentiation features in all of them. The examples below illustrate the point.

Principle: We have safe, welcoming classrooms where all students are valued and there are clear systems of classroom management

Ground rules, seating plans, classroom layout, displays, use of groups and classroom procedures are addressed here, and all help to create a climate which allows individuals to flourish.

Principle: The purpose of learning is clear to all

Many teachers share detailed lesson aims with paragraphs of text: objectives, outcomes, success criteria, and promptly lose or disengage all those for whom words are a challenge. The principles approach allows a variety of ways to access the lesson aims – visual maps, images and music, key words rather than paragraphs, and so on. If teachers are unable to engage learners and provide them with a clear purpose, then anxiety may set in and the remainder of the lesson will be uphill. Winning all hearts and minds is a key aspect of differentiation.

Principle: There is widespread participation in lessons

Using techniques to encourage the shy, to curb the dominant, to involve all in questioning etc. are all aspects of differentiation. Some lessons are characterised by participation by the few and passive acceptance by the majority. Differentiation is ensuring that all students participate, in mind and body; mental truancy is a real problem in some lessons.

Principle: Key terminology and language are developed in all lessons

Key word boxes, language games, speaking and listening activities, reading for understanding etc. are all important in supporting some and challenging others.

These principles are only examples. Schools adopting this approach will have principles related to the review of progress, deeper learning, scaffolding and challenge in the planning of tasks, integration of key skills, the development of social issues and a number of principles related to assessment including feedback and marking.

All of these have clear implications for differentiation and one of the most beneficial aspects of this approach is the potential for staff development. Asking curriculum or year teams to work together to develop techniques to meet each principle is a wonderful way of disseminating best practice. All school leaders know that they have Outstanding practitioners, but the challenge is to extend this practice to more classrooms. This process does exactly that.

Differentiation is at the heart of Outstanding classroom practice, so the idea that lesson-planning forms should require teachers to add something to a small box on a form – e.g. ‘pink worksheet for weaker learners’ – must be challenged. Visionary leadership teams are doing just that. Even Ofsted now make it clear that rigid lesson-planning structures are not necessary, and that ‘progress over time’ is the order of the day.

The most exhilarating aspect of the journey that schools take in developing policies and practice based on principles is the enthusiasm both of the teachers and support staff, who welcome an approach that values their professional judgement, and of the learners who experience lessons that are not only more creative, stimulating and diverse, but also more likely to meet their needs: differentiation in action. SR